The struggle to protect children from conspiracy theorist parents

Marianna SpringSocial media investigations correspondent

Marianna SpringSocial media investigations correspondent BBC

BBCThe inquest into the death of Paloma Shemirani, the daughter of a British conspiracy theorist, was like something out of a TV show.

As it unfolded, the medical world clashed with “Conspiracyland”, with experienced doctors questioned in courtrooms by people who believe in medical disinformation.

Paloma Shemirani, a Cambridge University graduate from East Sussex, died in July last year – seven months after being diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She had been told conventional treatment would give her a high chance of survival, but rejected chemotherapy in favour of alternative methods, like juices and coffee enemas.

Paloma’s twin brother Gabriel has long pointed the finger at their mother Kate. He strongly believes that Kate’s beliefs were behind Paloma’s decision to reject chemotherapy.

On Thursday, coroner Catherine Wood said Paloma was “highly influenced” by mother’s beliefs – as well as others including a family friend and her dad. They all advocated the alternative treatment she used.

“The influence that was brought to bear on Paloma… did contribute more than minimally to her death,” the coroner said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKate Shemirani, a former nurse with 80,000 followers on X, lost her licence to practise in 2021 – a Nursing and Midwifery Council committee found she had spread Covid-19 misinformation that “put the public at a significant risk of harm”.

Gabriel says that his childhood was engulfed by outlandish misinformation about 9/11 being “an inside job” and the Royal Family being shape-shifting lizards. Above all, he claims he and Paloma were subject to false health information.

When he last spoke to his mother on the phone, Gabriel says he vowed to, “hold [her] accountable”.

For her part, Kate Shemirani has remained firm that the decision to reject chemotherapy was entirely Paloma’s own and she has promoted a range of unproven theories holding the NHS and medics responsible for her death. Paloma’s father Faramarz Shemirani expressed similar views at the Coroner’s court.

Both during the inquest and when I contacted her about my original investigation, Kate repeatedly rejected any accusations that her beliefs or behaviour played a part in Paloma’s choices and her ultimately losing her life. Neither she nor Faramarz responded to my message asking for a comment on the inquest findings.

Yesterday, the coroner ruled: “I found Mrs Shemirani’s care of her daughter incomprehensible but not unlawful killing.

“It seems that if Paloma had been supported and encouraged to accept her diagnosis and considered chemotherapy with an open mind she probably would have followed that course.”

But this has raised broader questions around the influence and impact that conspiracy theories held by parents (where beliefs stretch far beyond genuine concerns) can have on children, including adult children.

And, in order to help protect children in the most extreme cases, where should the line be drawn between child protection and a parent’s freedom to raise their child according to their own beliefs?

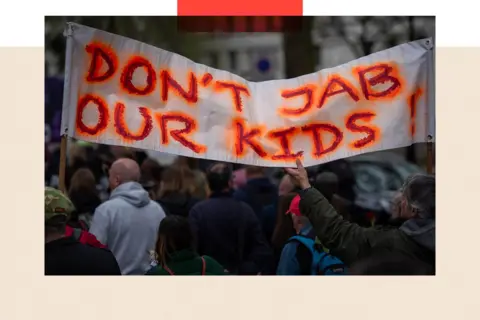

‘Massive rise’ in misinformation

Since I first investigated what had happened to Paloma, I’ve received dozens of messages from people concerned that their own relatives are making important decisions based on medical disinformation.

Several were from concerned grandparents, worried about their young grandchildren not being inoculated against certain diseases as a result of vaccine scepticism.

One grandmother emailed me, desperate for advice, as her daughter, wary of the MMR vaccine, was refusing to have her grandchild vaccinated.

When questioned, her daughter refused to change her decision, sending back pseudo-science from social media.

Declining uptake in the MMR jab, which protects against measles, mumps and rubella, has recently sparked concern among medics.

Last year, there were 2,911 laboratory-confirmed measles cases in England, the highest number recorded annually since 2012. So far this year, there have been more than 700 cases.

Earlier this year a child died in Liverpool after contracting measles.

Medical professionals have warned that anti-medicine conspiracy theories appear to have become more prevalent.

“I think Covid led to a massive rise in misinformation on social media, and before scientists could fact check it, or even knew about it… it was gathering pace,” says Liz O’Riordan, a former breast surgeon. “Trust in the medical profession began to drop.”

In her view, the consequences can be life threatening.

“Unvaccinated children are dying from measles. Boys are infertile from mumps infections. Families will grow up not trusting medical doctors – they won’t go for screening tests… Cancers will be picked up at a later stage increasing the risk of recurrence,” she argues.

“[Children] will hear conversations their parents have… Hearing information from people you know and trust will be more persuasive than hearing it from teachers or doctors.”

Age groups most susceptible

Liz O’Riordan, who herself has breast cancer, often debunks health misinformation online.

Several people who emailed me with concerns about their relative’s beliefs explained that they too had tried to check the legitimacy of those beliefs but found it difficult to figure out who was behind the misinformation.

This is a common problem: the credentials or motives of those spreading medical mistruths are often obscured.

But the power of the misinformation community itself can be part of the problem, warns Dr Timothy Hill, a senior lecturer at the University of Bath, who researches conspiracy theories. He describes it as “a large online and face-to-face community of people who are willing to take new people into the fold.”

Simply searching for information on a subject can sometimes lead people to it. “[People] end up in an algorithm-induced rabbit hole that backs up what their parents are saying,” says Ms O’Riordan.

As such, all sorts of people are susceptible to believing or considering misinformation.

A study published last year in the Political Psychology journal, which looked at survey data from almost 380,000 people internationally, suggests those aged under 35 are more inclined to believe in conspiracy theories compared to older groups.

“They often experience lower self-esteem, feel disconnected from politics, and are more likely to engage in unconventional political actions that challenge existing norms,” says Dr Hill.

Trusting parents vs the state

In theory, children should be protected. Any adult can raise concerns about a child’s wellbeing with the local authority, including if there’s a worry a child is being harmed by parental beliefs.

If it is then decided the child is at risk of harm, an application can be made to the family court for orders to protect them.

But in reality, legal experts tell me the threshold for intervention is high.

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty ImagesFamily lawyer Rachel Frost-Smith, legal director at Birketts LLP, recalls a case she worked on, relating to a young child and the mother’s anti-vaccine beliefs.

The mother was reluctant to provide information about the child’s vaccination status to the father, who Ms Frost-Smith represented. She had shown the father videos from social media to support her sceptical view of certain vaccinations.

“All of these were of the type of conspiracy theory genre, including a video stating that vaccinations cause autism,” recalls Ms Frost-Smith.

The court ruled the child could have its recommended vaccinations. However, in the UK there isn’t a law compelling vaccination – so if both parents agree they don’t want a child to be vaccinated, it would be unlikely to reach this verdict.

And the situation becomes more complicated still once the child turns 18.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe inquest heard how Paloma did speak with a social worker while living at home with her mum and remained adamant she did not want social services to be involved with her case. Her brother Gabriel had raised concerns and said he was disappointed Paloma was not visited in person.

Ms Frost-Smith says medics and social workers are limited in what they can do to protect adults, including those who seem to have “the capacity to make decisions even if they seem like ‘bad’ ones to other people”.

Changing the law: a debate

One remedy, advocated by some experts, is to change the law.

Michael Preston-Shoot, an emeritus professor of social work at the University of Bedfordshire, argues that legislation could be amended in England to make it possible for social workers to have a warrant to interview a person on their own – without needing to take legal action. This is already the case in Wales and Scotland.

“Sadly there are too many cases where practitioners cannot reach individuals because somebody else is getting in the way,” he says.

But Iain Mansfield, director of research at Policy Exchange, urges caution.

“I think this term ‘misinformation’ could be used to tilt that balance in quite a dangerous direction away from parents in favour of [the] state, which even if we trust it now to act well, it might not act well in future.”

“It really comes back to who defines misinformation,” he continues. “Who are you giving that power to? Do you want to give the power to a government? Do you want to give it to a large corporation or an individual billionaire?

“I think we need to err on the side of trusting parents here.”

‘The truth isn’t sexy or exciting’

Then there is the question of how much responsibility social media sites should bear.

The Online Safety Act, introduced in the UK in 2023, requires major social media companies to make commitments to removing illegal content and protect children from harmful posts – but it’s less clear-cut when it comes to dealing with legal content that could be considered harmful.

There’s a complex environment surrounding social media regulation too, including on X where Elon Musk has changed rules around moderation since taking the helm.

“It is impossible to get above the noise as the truth isn’t sexy or exciting, and most doctors and scientists don’t have the time or skills to counteract this,” says Liz O’Riordan.

For her, the current levels of social media regulation are not enough. Yet Mr Mansfield again warns caution about changing the rules to rely more on social media companies to determine what is safe.

“I would be very cautious about saying that we think large corporations, whoever they’re owned by, should be taking a lead in deciding what’s misinformation and what we should be censoring.”

So could the solution be broader, not involving regulation at government or corporate level at all – but instead equipping users themselves to better determine what is true?

Learning to spot red flags

“[We should] teach children at school how to interpret medical claims they see online, how to fact-check, think for themselves, not to trust everything they see or hear,” argues Ms O’Riordan.

She wants them to, as she puts it, recognise red flags – and “give them the courage to question what their parents say”.

This all lends to what Gabriel says he experienced too.

For him, “the oxygen of conspiracy theories is isolation”. Once at secondary school and away from his home, he was “forced to question [his] beliefs as people disagreed”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNeither Kate Shemirani nor Faramarz Shemirani responded to my requests for an interview ahead of the inquest conclusion.

They previously wrote to the BBC saying they have evidence “Paloma died as a result of medical interventions given without confirmed diagnosis or lawful consent”. The BBC has seen no evidence to substantiate these claims.

Gabriel, however, sees his twin sister’s inquest as a wake up call – for too long, he thinks society has let down those whose parents believe conspiracy theories.

“We as a society need to stop making conspiracy theorists into circus animals,” he argues, as they are not “harmless”.

“We also need to realise, as well, that the road to becoming a conspiracy theorist is far shorter than you think.”

Hear more on the new podcast episode of Marianna in Conspiracyland 2 on BBC Sounds. Also, watch the recent Panorama documentary, Cancer conspiracy theories: Why did our Sister Die? on iPlayer

Top picture credits: Matthew Chattle/Future Publishing via Getty Images and Press Association

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Share this content:

إرسال التعليق